NIOSH Worker Health Chartbook, 2004: Excerpts

Summary Statement

An excerpt from a chartbook that includes figures and tables describing the magnitude, distribution, and trends of the Nation’s occupational injuries, illnesses, and fatalities. The excerpt includes information on construction. A link to the entire PDF can be found here: http://www.cpwr.com/sites/default/files/publications/5th%20Edition%20Chart%20Book%20Final.pdf

Sep 2004

This document is in the public domain and may be freely copied or reprinted.

DisclaimerMention of any company or product does not constitute endorsement by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH). In addition, citations to Web sites external to NIOSH do not constitute NIOSH endorsement of the sponsoring organizations or their programs or products. Furthermore, NIOSH is not responsible for the content of these Web sites.

Ordering Information

To receive documents or other information about occupational safety and health topics, contact NIOSH at

NIOSH

Publications Dissemination

4676 Columbia Parkway

Cincinnati, OH 45226–1998

Telephone: 1–800–35–NIOSH (1–800–356–4674)

Fax: 513–533–8573

E-mail: pubstaft@cdc.gov

or visit the NIOSH Web site at www.cdc.gov/niosh

DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2004–146

September 2004

Abstract

The Worker Health Chartbook, 2004 is a descriptive epidemiologic reference on occupational morbidity and mortality in the United States. The Chartbook includes more than 400 figures and tables describing the magnitude, distribution, and trends of the Nation’s occupational injuries, illnesses, and fatalities. This 2004 edition of the Worker Health Chartbook builds on the foundation established in the first edition, published in 2000. The Chartbook is intended as a resource for technical and nontechnical audiences, including agencies, organizations, employers, researchers, workers, and others who need to know about occupational injury and illness. This concise, chart-based document consolidates information from the network of monitoring systems that forms the cornerstone of injury and illness surveillance in the United States. The document is intended to fulfill the NIOSH strategic goals for preventing occupational injury and illness and to guide research and prevention efforts.

The Worker Health Chartbook, 2004 contains five chapters and three appendices. Chapter 1 describes the U.S. labor force and the health status of workers. Chapter 2 focuses on the demographic characteristics of workers (age, sex, occupation, industry, and case severity) and 33 types of occupational injuries and illnesses that affect them: amputations; anxiety, stress, and neurotic disorders; asbestosis; asthma; back, including spine and spinal cord; bloodborne infections and percutaneous exposures; bruises and contusions; byssinosis; carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS); coal workers’ pneumoconiosis (CWP); cuts and lacerations; dermatitis; disorders due to physical agents; disorders associated with repeated trauma; dust diseases of the lungs; fatal injuries; fractures; hearing loss; heat burns and scalds; hypersensitivity pneumonitis; lead toxicity; mesothelioma; musculoskeletal disorders; nonfatal injury; pneumoconioses; poisoning; respiratory diseases; respiratory conditions due to toxic agents; silicosis; skin diseases and disorders; sprains, strains, and tears; tendonitis; and tuberculosis. Chapter 2 also examines the magnitude, trends, and geographic distribution of these conditions. Chapter 3 focuses exclusively on agriculture, presenting data on fatal and nonfatal injuries among adults and children in agriculture and examining selected health conditions of farm workers. Chapter 4 concentrates on high-risk industries and occupations and reflects NIOSH research priorities in mining and construction. Chapter 5 addresses special populations, exploring available occupational injury and illness data on young workers, older workers, and Hispanic workers.

The three appendices complement the chapters with details about source data and programs. Appendix A describes the 21 survey and surveillance programs used by the contributors; it includes program contacts and reference citations for follow-up by users. Appendix B examines various aspects of data collection, analysis methods, and dissemination practices that limit the uses and inferences of data. Appendix C provides a bibliography of reference materials from the public domain, including data tables, report forms and documentation, government news releases, and research articles.

Chapter 4: High-Risk Industries and Occupations

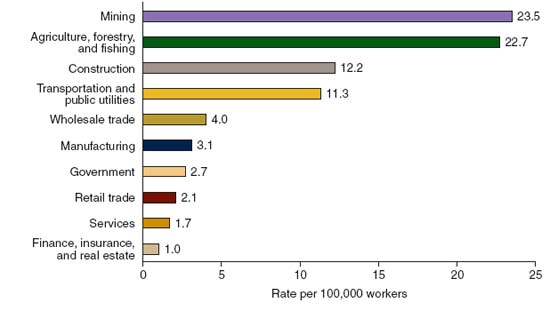

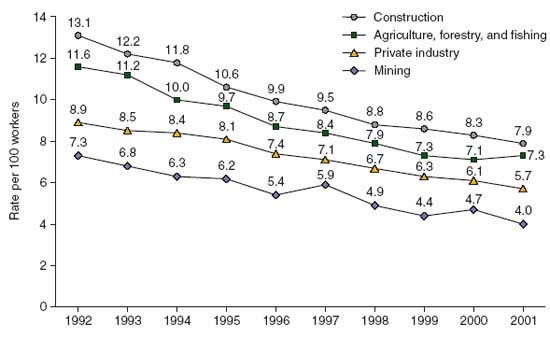

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) conducts comprehensive surveillance and research programs focused on selected high-risk industrial sectors such as agriculture, mining, and construction. Historically, workers in these industries have suffered the highest rates of fatal injury. The most recent data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries (CFOI) reveal that fatal injury rates in these high-risk industries range from 3.0 to 5.6 times the private industry rate of 4.2 per 100,000 workers (Figure 4–1) [BLS 2003a]. Except for mining, these high-risk industries also have elevated rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses, as shown by data from the BLS annual Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses (SOII) (Figure 4–2).

This chapter provides data on nonfatal and fatal injuries and illnesses in the mining* and construction industries as well as associated occupations. Similar data for the agriculture industry are provided in Chapter 3.

*The Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) provides BLS with data conforming to the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) defi nitions for “mining operators in coal, metal, and nonmetal mining.” Readers should note the following within the BLS data: (1) mining includes oil and gas extraction, and (2) independent mining contractors are excluded from the coal, metal, and nonmetal mining industries.

Figure 4–1. Fatal occupational injury rates by industry division, 2002. Fatal occupational injury rates in 2002 were highest in mining (23.5 per 100,000 workers), agriculture, forestry, and fishing (22.7), construction (12.2), and transportation and public utilities (11.3). The rate for all private industry was 4.2 per 100,000 workers. (Source: BLS [2003a].)

Figure 4–2. Incidence rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses in private industry and in high-risk industrial sectors, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001, the rates of total recordable injuries and illnesses in construction and agriculture exceeded those for all private industry by an average of 37% and 22%, respectively. However, the rates all decreased by similar percentages during this period—36% for all private industry, 40% for construction, and 37% for agriculture, forestry, and fishing. (Source: BLS [2002a].)

Construction Trades

This section provides data for tracking trends in fatal and nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses among workers in the construction trade. An estimated 9.6 million persons were employed in the construction industry in 2001. Most of these workers were aged 25–54 (75.4%), male (90.3%), and white (90.8%) [BLS 2001].

Over the years, construction has ranked among industries with the highest rates of both fatal and nonfatal occupational injuries. BLS reported that the number and rate of fatal occupational injuries in the construction sector in 2001 were the highest recorded since the inception of CFOI (1,225 fatal occupational injuries with an incidence rate of 13.3 per 100,000 employed workers) [BLS 2002b]. For the same year, BLS reported that the construction industry experienced 481,400 nonfatal injuries and illnesses at a rate of 7.9 per 100 full-time workers in the industry [BLS 2002a].

Since the early 1990s, NIOSH has supported extensive extramural surveillance and research on the construction sector of private industry. CPWR – Center for Construction Research and Training (CPWR) is a principal partner of NIOSH in conducting these activities. Early efforts focused on surveillance data and surveillance research, including the preparation of the first of three chart books focusing on construction safety and health issues [Pollack and Chowdhury 2001].

The underlying data for Figures 4–20 through 4–52 come from a number of the BLS statistical programs, including the Current Population Survey (CPS), CFOI, and SOII. The CPS provides data for estimating the construction trade occupation denominators used for many of the rate estimates. The CPWR uses CFOI to characterize occupational fatalities and SOII to characterize nonfatal injuries and illnesses. Twelve construction trade occupations are the principal focus of this section:

- Brickmasons

- Carpenters

- Drywall installers

- Electricians

- Ironworkers

- Construction laborers

- Operating engineers

- Painters

- Plumbers

- Roofers

- Truck drivers

- Welders and cutters

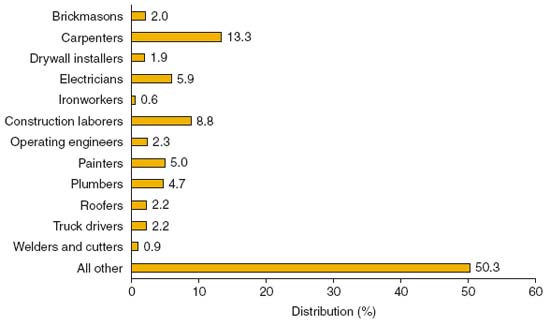

Among the trades monitored by CPWR, the estimated distribution

of employed construction workers by trade ranged from 0.6% to

13.3% during 1992–2001. Carpenters made up the largest proportion

of construction workers (13.3%), followed by construction

laborers (8.8%) and electricians (5.9%) (Figure 4–20). The construction

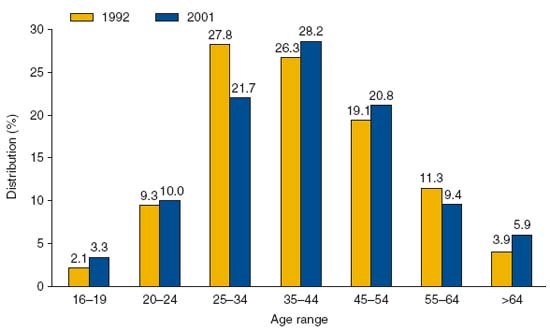

workforce has been growing older: In 2001, the average

age for construction workers was 38.7 (1.5 years older than it was

in 1992). In addition, the median age increased from 35 to 39 during

this 10-year period. The aging of the construction workforce

is reflected in the distribution of fatal occupational injuries in this

group by age (Figure 4–21). From 1992 to 2001, the largest proportion

of fatal occupational injuries shifted from construction workers

aged 25–34 to those aged 35–44. For construction workers aged

25 or 34, the proportion with fatal injuries declined (from 27.8%

to 21.7%), whereas it increased for workers aged 65 or older (from

3.9% to 5.9%).

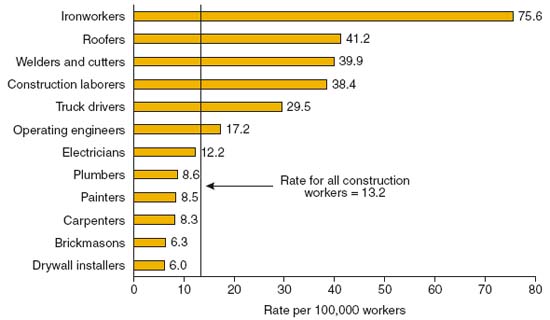

Fatal occupational injury rates in the construction trades for 2001

ranged from 6.0 per 100,000 full-time workers for drywall installers to 75.6 for ironworkers—more than a 12-fold difference (Figure

4–23). Falls to lower level accounted for the highest number of

fatal injuries among construction workers (410 or 4.3 per 100,000

full-time workers), and highway accidents accounted for the next

highest number (161 or 1.7 per 100,000 full-time workers) (Figure

4–25). This section includes figures that chart fatal injury rates for

each of the 12 construction trades that form our focus. For each

trade, the figure contrasts fatal occupational injury rates for all

construction workers during each year from 1992 through 2001

(Figures 4–29, 4–31, 4–33, 4–35, 4–37, 4–39, 4–41, 4–43, 4–45, 4–47,

4–49, and 4–51).

Rates of nonfatal injuries and illnesses involving days away from

work in the construction trades in 2001 ranged from 131.2 per

10,000 full-time workers for painters to 751.8 for ironworkers—

nearly a 6-fold difference (Figure 4–27). Injuries and illnesses associated

with ergonomic events or exposures made up 26.5% (49,237

of 185,662) of all nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving

days away from work in the construction industry in 2001 [BLS

2003c]. The rate of bending, climbing, crawling, reaching, twisting

injuries in construction was 15 per 10,000 full-time workers—nearly

double the rate of 8 for all private industry that year (Figure 4–28).

This section includes figures that chart nonfatal injury and illness

rates for each of the 12 construction trades that form our focus. For

each trade, the figure contrasts nonfatal injury and illness rates for

all construction workers during each year from 1992 through 2001

(Figures 4–30, 4–32, 4–34, 4–36, 4–38, 4–40, 4–42, 4–44, 4–46, 4–48,

4–50, and 4–52).

Distribution of Construction Workers

by Trade

How were construction workers distributed by major

construction trade during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–20. Average distribution of full-time construction

workers by trade, 1992–2001. Among the trades monitored

by CPWR, the estimated distribution of employed construction

workers by trade ranged from 0.6% to 13.3% during

1992–2001. Carpenters made up the largest proportion of

construction workers (13.3%), followed by construction laborers

(8.8%) and electricians (5.9%). (Notes: (1) Apprentices are

included for some trades when data were available. (2) All other

includes managers, professionals, supervisors, clerical workers,

sales personnel, and trades that each totaled less than 1% of

the industry. (3) Computations were based on a definition of

full-time work as 2,000 employee hours per year.) (Sources: BLS

[2002c]; Dong et al. [2004].)

Fatal Injuries

Age

How did the numbers and rates of fatal occupational

injuries in construction workers vary by age during 1992

and 2001?

Figure 4–21. Distribution of fatal occupational injuries among

construction workers by age, 1992 and 2001. The construction

workforce has been growing older: In 2001, the average age

for construction workers was 38.7 (1.5 years older than it was

in 1992). In addition, the median age increased from 35 to

39 during this 10-year period. The aging of the construction

workforce is reflected in the distribution of fatal occupational

injuries in this group by age. From 1992 to 2001, the largest

proportion of fatal occupational injuries shifted from construction

workers aged 25–34 to those aged 35–44. For construction

workers aged 25 or 34, the proportion with fatal injuries

declined (from 27.8% to 21.7%), whereas it increased for

workers aged 65 or older (from 3.9% to 5.9%). (Sources: BLS

[2002b,c]; Dong et al. [2004].)

Race/Ethnicity

How did fatal occupational injury rates differ between

Hispanic and non-Hispanic construction workers during

1992–2001?

Figure 4–22. Fatal occupational injury rates among Hispanic

and non-Hispanic workers in the construction industry, 1992– 2001. Fatal occupational injuries

among Hispanic construction workers increased from 108 in 1992 to 281 in 2001. Since 1992,

Hispanic construction workers have had markedly higher fatal

occupational injury rates than their non-Hispanic counterparts.

In 2001 (the most recent year measured), the rate of

work-related deaths from construction injuries for Hispanics

was 19.5 per 100,000 full-time workers—62.5% higher than

the rate of 12.0 for non-Hispanic construction workers. During

1990–2001, Hispanic employment in the U.S. construction

industry increased greatly, from 649,800 in 1990 to 1.5 million

(or 15.6% of the construction workforce) in 2001. (Sources: BLS

[2002b,c]; Dong et al. [2004].)

Occupation

How did the fatal occupational injury rates differ by

construction trade in 2001?

Figure 4–23. Fatal occupational injury rates by construction

trade, 2001. Fatal occupational injury rates in the construction

trades for 2001 ranged from 6.0 per 100,000 full-time workers

for drywall installers to 75.6 for ironworkers—more than a 12-

fold difference. (Sources: BLS [2002b,c]; Chowdhury and Dong

[2002].)

Establishment Size

How did fatal occupational injury rates vary by

employment size of establishment?

Figure 4–24. Distribution of construction workers and fatal

occupational injuries by employment size of establishment,

2001. In 2001, more than 80% of construction establishments had

fewer than 10 employees, and establishments with fewer than 20

employees employed only 38.2% of the wage-and-salary workforce.

However, fatal occupational injuries among these smaller establishments

accounted for more than 55.5% of fatal occupational

injuries in 2001. (Note: The calculation excludes the self-employed

workers and deaths reported without establishment-size information.)

(Sources: BLS [2002b,c]; Census [2003]; Dong et al. [2004].)

Event or Exposure

How did the numbers and rates of fatal occupational

injuries differ by fatal event in 2001?

Figure 4–25. Numbers and rates of fatal occupational injuries

among construction workers by fatal event, 2001. In 2001, falls

to lower level accounted for the greatest number of fatal occupational

injuries among construction workers (410 fatalities or

4.3 per 100,000 full-time workers). Highway accidents accounted

for 161 deaths, a fatal injury rate of 1.7 per 100,000 full-time

workers. (Sources: BLS [2002b,c]; Dong et al. [2004].)

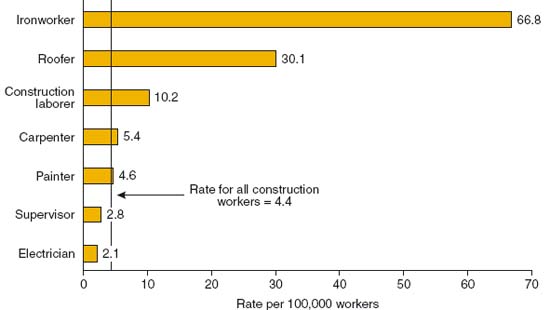

How did fatal fall rates differ by construction trade in

2001?

Figure 4–26. Fatal occupational fall rates by selected construction

trade, 2001. The 2001 rate for fatal occupational falls

among ironworkers was 66.8 per 100,000 workers—15 times

the average rate for all construction. For roofers, the fatal fall

rate was 30.1, or 7 times the average rate for all construction.

(Sources: BLS [2002b,c]; Dong et al. [2004].)

Nonfatal Injuries and Illnesses

Occupation

How did the rate of nonfatal occupational injury and

illness differ by construction trade in 2001?

Figure 4–27. Rate of nonfatal occupational injury and illness

cases with days away from work by construction trade, 2001. In

2001, the rate of nonfatal injuries and illnesses involving days

away from work ranged from 131.2 per 10,000 full-time workers

among painters to 751.8 for ironworkers—nearly a 6-fold

difference. (Sources: BLS [2002c; 2003b]; Pollack and Chowdhury

[2001]; Dong et al. [2004].)

Event or Exposure

How did rates of nonfatal occupational injury and illness

differ by type of ergonomic exposure in construction and

all private industry in 2001?

Figure 4–28. Rates of nonfatal occupational injury and illness

cases with days away from work in construction and private

industry by selected ergonomic events or exposures, 2001.

Injuries and illnesses associated with ergonomic events or

exposures made up 26.5% (49,237 of 185,662) of all nonfatal

occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away from

work in the construction industry in 2001. The rate of bending,

climbing, crawling, reaching, twisting injuries in construction

was 15 per 10,000 full-time workers—nearly double the

rate of 8 for all private industry that year. (Sources: BLS [2002c;

2003b,c]; Dong et al. [2004].)

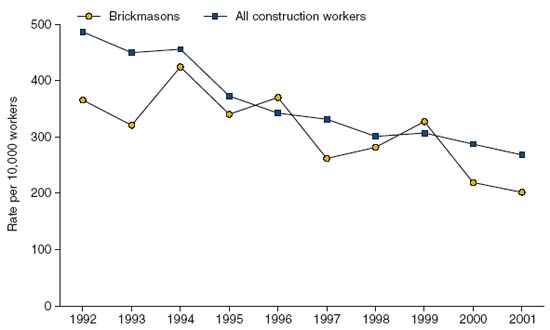

Brickmasons

Fatal Injuries

How did the fatal occupational injury rates for

brickmasons compare with those for all construction

workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–29. Fatal occupational injury rates for brickmasons

and all construction workers, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001,

fatal occupational injury rates for brickmasons were generally

lower than those for all construction workers. Rates for brickmasons

showed an up-and-down decreasing pattern, varying

from 6.3 per 100,000 full-time workers in 2001 to 15.2 in 1995.

BLS reported 145 fatal occupational injuries among brickmasons

during this 10-year period—an average of 14 fatalities per

year. (Sources: BLS [2002b,c]; Pollack and Chowdhury [2001];

Chowdhury and Dong [2003].)

Nonfatal Injuries and Illnesses

How did the rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and

illnesses for brickmasons compare with those for all

construction workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–30. Rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

involving days away from work for brickmasons and all

construction workers, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001, rates of

nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away

from work were generally lower for brickmasons than for all

construction workers. Rates for brickmasons showed a downward

trend from a 424 per 10,000 full-time workers in 1994

to 201 in 2001. BLS reported 36,172 nonfatal occupational

injuries and illnesses among brickmasons during this 10-year

period—an average of 3,617 nonfatal cases per year. (Sources:

BLS [2002c; 2003b]; Pollack and Chowdhury [2001]; Dong et al.

[2004].)

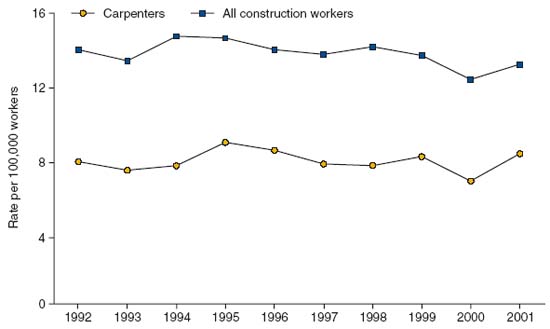

Carpenters

Fatal Injuries

How did the fatal occupational injury rates for carpenters

compare with those for all construction workers during

1992–2001?

Figure 4–31. Fatal occupational injury rates for carpenters

and all construction workers, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001,

fatal occupational injury rates for carpenters were parallel to

and consistently lower than rates for all construction workers.

Rates for carpenters varied within a narrow range, from 8.9 per

100,000 full-time workers in 1995 to 6.7 in 2000. BLS reported

848 fatal occupational injuries among carpenters during this

10-year period—an average of 85 fatalities per year. (Sources:

BLS [2002b,c]; Pollack and Chowdhury [2001]; Chowdhury and

Dong [2003].)

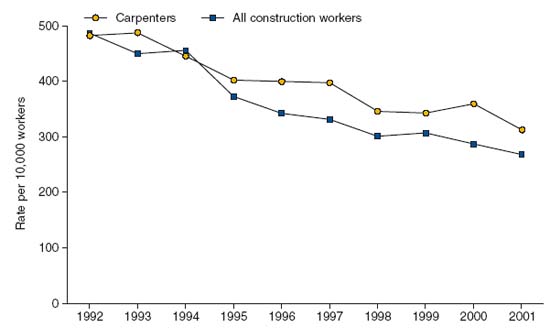

Nonfatal Injuries and Illnesses

How did the rates of nonfatal occupational injuries

and illnesses for carpenters compare with those for all

construction workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–32. Rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

involving days away from work for carpenters and all

construction workers, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001, rates of

nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away

from work were slightly higher for carpenters than for all construction

workers, but they were comparable in overall magnitude.

Rates for carpenters showed a downward trend, from

489 per 10,000 full-time workers in 1993 to 313 in 2001. BLS

reported 285,705 nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

among carpenters during this 10-year period—an average of

28,570 nonfatal cases per year. (Sources: BLS [2002c; 2003b]; Pollack

and Chowdhury [2001]; Dong et al. [2004].)

Drywall Installers

Fatal Injuries

How did the fatal occupational injury rates for drywall

installers compare with those for all construction workers

during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–33. Fatal occupational injury rates for drywall installers

and all construction workers, 1992–2001. Fatal occupational

injury rates for drywall installers were consistently lower than

those for all construction workers during 1992–2001. Except

for 1992, the rates for drywall installers varied within a narrow

range, from 6.7 per 100,000 full-time workers in 1993 to 3.4

in 1998. BLS reported 80 fatal occupational injuries among

drywall installers during this 10-year period—an average of 10

fatalities per year. (Sources: BLS [2002b,c]; Pollack and Chowdhury

[2001]; Chowdhury and Dong [2003].)

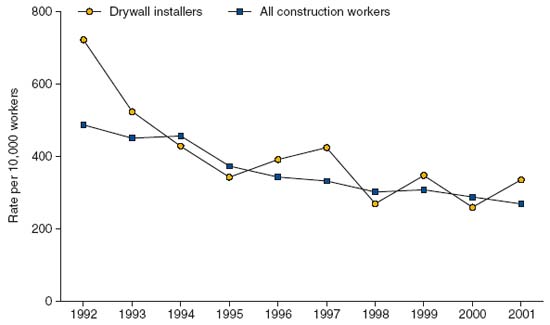

Nonfatal Injuries and Illnesses

How did the rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and

illnesses for drywall installers compare with those for all

construction workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–34. Rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

involving days away from work for drywall installers and

all construction workers, 1992–2001. Rates of nonfatal occupational

injuries and illnesses involving days away from work for

drywall installers showed a downward trend during 1992–2001,

from 720 per 10,000 full-time workers in 1992 to 259 in 2000.

BLS reported 43,575 nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

among construction workers during this 10-year period—an

average of 4,357 nonfatal cases per year. (Sources: BLS [2002c;

2003b]; Pollack and Chowdhury [2001]; Dong et al. [2004].)

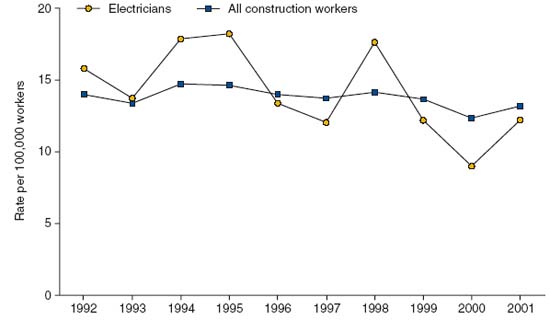

Electricians

Fatal Injuries

How did the fatal occupational injury rates for electricians

compare with those for all construction workers during

1992–2001?

Figure 4–35. Fatal occupational injury rates for electricians

and all construction workers, 1992–2001. Fatal occupational

injury rates for electricians during 1992–2001 were comparable

with those for all construction workers. Rates for electricians

showed an up-and-down decreasing pattern, from 18.3 per

100,000 full-time workers in 1995 to 9.0 in 2000. BLS reported

671 fatal occupational injuries among electricians during this

10-year period—an average of 67 fatalities per year. (Sources:

BLS [2002b,c]; Pollack and Chowdhury [2001]; Chowdhury and

Dong [2003].)

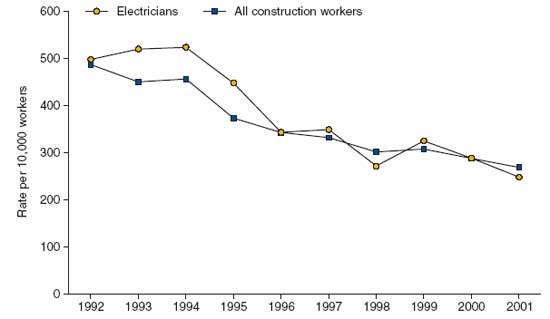

Nonfatal Injuries and Illnesses

How did the rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and

illnesses for electricians compare with those for all

construction workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–36. Rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

involving days away from work for electricians and all

construction workers, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001, rates of

nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away

from work for electricians were slightly higher but comparable

with those for all construction workers. Rates for electricians

showed a downward trend, from 522 per 10,000 full-time workers

in 1994 to 246 in 2001. BLS reported 142,811 nonfatal occupational

injuries and illnesses among electricians during this

10-year period—an average of 14,281 nonfatal cases per year.

(Sources: BLS [2002c; 2003b]; Pollack and Chowdhury [2001];

Dong et al. [2004].)

Ironworkers

Fatal Injuries

How did the fatal occupational injury rates for ironworkers

compare with those for all construction workers during

1992–2001?

Figure 4–37. Fatal occupational injury rates for ironworkers

and all construction workers, 1992–2001. Fatal occupational

injury rates for ironworkers during 1992–2001 were substantially

greater (4.8–10.5 times greater) than those for all construction

workers. Rates for ironworkers showed a downward

trend, from 147.6 per 100,000 full-time workers in 1992 to 60.0

in 2000. BLS reported 424 fatal occupational injuries among

ironworkers during this 10-year period—an average of 42 fatalities

per year. (Sources: BLS [2002b,c]; Pollack and Chowdhury

[2001]; Chowdhury and Dong [2003].)

Nonfatal Injuries and Illnesses

How did the rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and

illnesses for ironworkers compare with those for all

construction workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–38. Rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

involving days away from work for ironworkers and

all construction workers, 1992–2001. Rates of nonfatal occupational

injuries and illnesses involving days away from work

for ironworkers during 1992–2001 were consistently greater

(1.7–3.9 times greater) than those for all construction workers.

Rates for ironworkers showed a downward trend, from

1,750 per 10,000 full-time workers in 1992 to 550 in 1997. The

2001 rate of 752 per 10,000 full-time workers represents a 57%

decrease from the 1992 rate of nonfatal injury and illness for

ironworkers. BLS reported 40,173 cases of nonfatal occupational

injuries and illnesses among ironworkers during this

10-year period—an average of 4,017 nonfatal cases per year.

(Sources: BLS [2002c; 2003b]; Pollack and Chowdhury [2001];

Dong et al. [2004].)

Construction Laborers

Fatal Injuries

How did the fatal occupational injury rates for

construction laborers compare with those for all

construction workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–39. Fatal occupational injury rates for construction

laborers and all construction workers, 1992–2001. Fatal occupational

injury rates for construction laborers during 1992–2001

were substantially greater (2.5–3.4 times greater) than those

for all construction workers. Between 1992 and 1997, rates

increased from 36.8 per 100,000 full-time workers to 47.3, then

decreased to a low of 30.8 in 2000. BLS reported 2,873 fatal

occupational injuries among construction laborers during this

10-year period—an average of 287 fatalities per year. (Sources:

BLS [2002b,c]; Pollack and Chowdhury [2001]; Chowdhury and

Dong [2003].)

Nonfatal Injuries and Illnesses

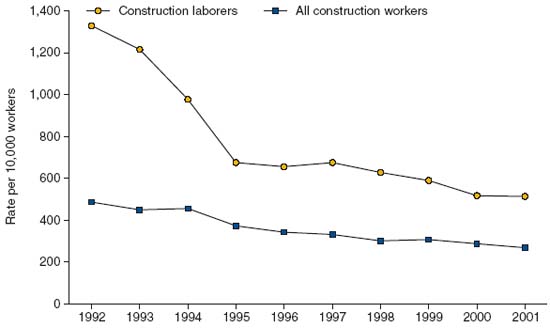

How did the rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and

illnesses for construction laborers compare with those for

all construction workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–40. Rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

involving days away from work for construction laborers

and all construction workers, 1992–2001. Rates of nonfatal

occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away

from work for construction laborers during 1992–2001 were

consistently greater (1.8–2.7 times greater) than those for all

construction workers. Rates for construction laborers showed

a downward trend, from 1,330 per 10,000 full-time workers in

1992 to 512 in 2001. The 2001 rate represents a 62% decrease

from the 1992 rate. BLS reported 467,258 nonfatal occupational

injuries and illnesses among construction laborers during

this 10-year period—an average of 46,726 nonfatal cases

per year. (Sources: BLS [2002c; 2003b]; Pollack and Chowdhury

[2001]; Dong et al. [2004].)

Operating Engineers

Fatal Injuries

How did the fatal occupational injury rates for operating

engineers compare with those for all construction workers

during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–41. Fatal occupational injury rates for operating

engineers and all construction workers, 1992–2001. Fatal occupational

injury rates for operating engineers during 1992–2001

exceeded those for all construction workers except during 1995.

Rates for operating engineers showed an increasing trend, varying

between 12.2 per 100,000 full-time workers and 23.0 (compared

with 12.4 and 14.8 per 100,000 full-time workers for all

construction workers). BLS reported 342 fatal occupational injuries

among operating engineers during this 10-year period—an

average of 34 fatalities per year. (Sources: BLS [2002b,c]; Pollack

and Chowdhury [2001]; Chowdhury and Dong [2003].)

Nonfatal Injuries and Illnesses

How did the rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and

illnesses for operating engineers compare with those for

all construction workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–42. Rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

involving days away from work for operating engineers

and all construction workers, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001,

rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving

days away from work were lower for operating engineers than

for all construction workers, but both rates were comparable

in overall magnitude. Rates for operating engineers showed a

downward trend, from 581 per 10,000 full-time workers in 1992

to 162 in 2001. BLS reported 37,431 nonfatal occupational

injuries and illnesses among operating engineers during this

10-year period—an average of 3,743 nonfatal cases per year.

(Sources: BLS [2002c; 2003b]; Pollack and Chowdhury [2001];

Dong et al. [2004].)

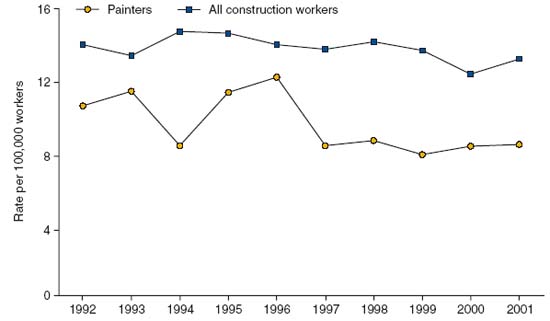

Painters

Fatal Injuries

How did the fatal occupational injury rates for painters

compare with those for all construction workers during

1992–2001?

Figure 4–43. Fatal occupational injury rates for painters and

all construction workers, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001, fatal

occupational injury rates for painters were lower than those

for all construction workers. Rates for painters showed an upand-

down decreasing pattern, varying from 12.2 per 100,000

full-time workers in 1996 to 7.9 in 1999. BLS reported 384 fatal

occupational injuries among painters during this 10-year period—

an average of 38 fatalities per year. (Sources: BLS [2002b,c];

Pollack and Chowdhury [2001]; Chowdhury and Dong [2003].)

Nonfatal Injuries and Illnesses

How did the rates of nonfatal occupational injuries

and illnesses for painters compare with those for all

construction workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–44. Rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and

illnesses involving days away from work for painters and all

construction workers, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001, rates of

nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away

from work for painters were consistently lower (0.5 to 0.8 times

lower) than those for all construction workers. Rates showed

a downward trend, from 368 per 10,000 full-time workers in

1992 to 131 in 2001. The 2001 rate of 131 per 10,000 full-time

workers represents a 64% decrease in rates since 1992. BLS

reported 50,264 nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

among painters during this 10-year period—an average of

5,026 nonfatal cases per year. (Sources: BLS [2002c; 2003b]; Pollack

and Chowdhury [2001]; Dong et al. [2004].)

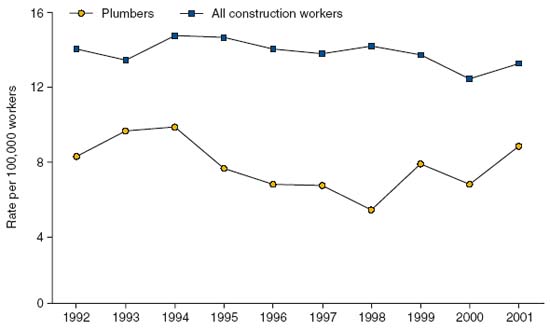

Plumbers

Fatal Injuries

How did the fatal occupational injury rates for plumbers

compare with those for all construction workers during

1992–2001?

Figure 4–45. Fatal occupational injury rates for plumbers

and all construction workers, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001,

fatal occupational injury rates for plumbers were lower than

those for all construction workers. Rates for plumbers showed

a downward trend, from 9.7 per 100,000 full-time workers in

1994 to 5.1 in 1998. BLS reported 284 fatal occupational injuries

among plumbers during this 10-year period—an average of

28 fatalities per year. (Sources: BLS [2002b,c]; Pollack and Chowdhury

[2001]; Chowdhury and Dong [2003].)

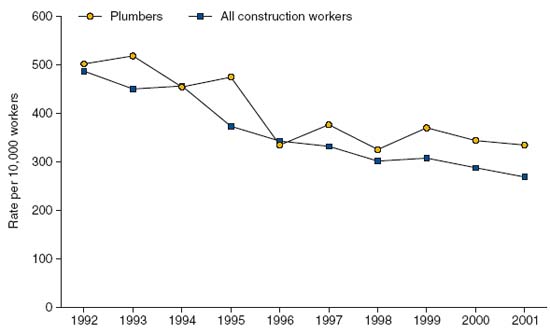

Nonfatal Injuries and Illnesses

How did the rates of nonfatal occupational injuries

and illnesses for plumbers compare with those for all

construction workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–46. Rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

involving days away from work for plumbers and all

construction workers, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001, rates of

nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away

from work for plumbers were slightly higher than those for all

construction workers, though they were comparable in overall

magnitude. Rates for plumbers showed a downward trend,

from 504 per 10,000 full-time workers in 1992 to 326 in 1998.

BLS reported 113,679 nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

among plumbers during this 10-year period—an average

of 11,370 nonfatal cases per year. (Sources: BLS [2002c; 2003b];

Pollack and Chowdhury [2001]; Dong et al. [2004].)

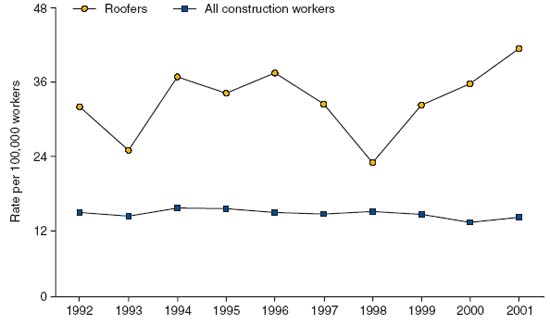

Roofers

Fatal Injuries

How did the fatal occupational injury rates for roofers

compare with those for all construction workers during

1992–2001?

Figure 4–47. Fatal occupational injury rates for roofers and

all construction workers, 1992–2001. Fatal occupational injury

rates for roofers were 1.6–2.8 times greater than those for all

construction workers during 1992–2001. Rates followed an upand-

down increasing pattern, with a high of 41.2 per 100,000

full-time workers in 2001 and a low of 22.3 in 1998. BLS reported

569 fatal occupational injuries among roofers during this

10-year period—an average of 57 fatalities per year. (Sources:

BLS [2002b,c]; Pollack and Chowdhury [2001]; Chowdhury and

Dong [2003].)

Nonfatal Injuries and Illnesses

How did the rates of nonfatal occupational injuries

and illnesses for roofers compare with those for all

construction workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–48. Rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and

illnesses involving days away from work for roofers and all

construction workers, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001, rates

of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days

away from work were consistently greater for roofers (1.1–1.8

times greater) than for all construction workers. Rates for roofers

showed a downward trend, from 838 per 10,000 full-time

workers in 1994 to 325 in 1998. BLS reported 61,539 nonfatal

occupational injuries and illnesses among roofers during this

10-year period—an average of 6,154 nonfatal cases per year.

(Sources: BLS [2002c; 2003b]; Pollack and Chowdhury [2001];

Dong et al. [2004].)

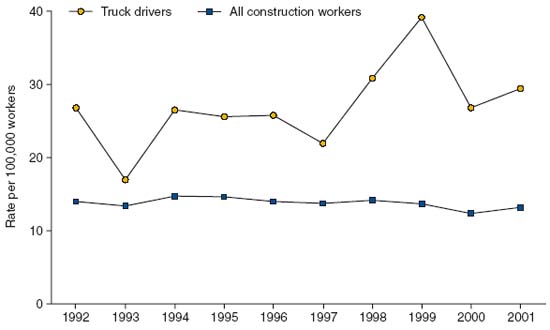

Truck Drivers

Fatal Injuries

How did the fatal occupational injury rates for truck

drivers compare with those for all construction workers

during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–49. Fatal occupational injury rates for truck drivers

and all construction workers, 1992–2001. Fatal occupational

injury rates for truck drivers were 1.3–2.9 times greater than

those for all construction workers during 1992–2001. Rates

for truck drivers showed a down-and-up pattern, with a low of

17.0 per 100,000 full-time workers in 1993 and a high of 39.2

in 1999. BLS reported 479 fatal occupational injuries among

truck drivers during this 10-year period—an average of 48 fatalities

per year. (Sources: BLS [2002b,c]; Pollack and Chowdhury

[2001]; Chowdhury and Dong [2003].)

Nonfatal Injuries and Illnesses

How did the rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and

illnesses for truck drivers compare with those for all

construction workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–50. Rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

involving days away from work for truck drivers and all

construction workers, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001, rates of

nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving days away

from work for truck drivers usually exceeded rates for all construction

workers. Rates for truck drivers varied from 533 per

10,000 full-time workers in 1992 to 359 in 1998. BLS reported

57,999 nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses among

truck drivers during this 10-year period—an average of 5,800

nonfatal cases per year. (Sources: BLS [2002c; 2003b]; Pollack and

Chowdhury [2001]; Dong et al. [2004].)

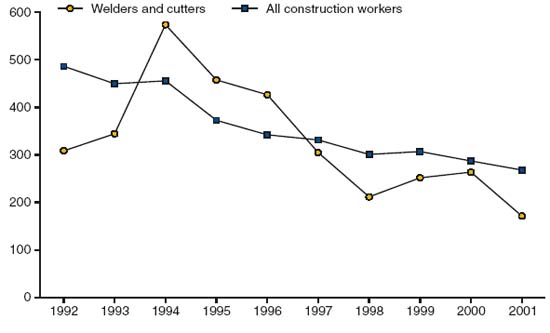

Welders and Cutters

Fatal Injuries

How did the fatal occupational injury rates for welders

and cutters compare with those for all construction

workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–51. Fatal occupational injury rates for welders and cutters

and all construction workers, 1992–2001. Fatal occupational

injury rates for welders and cutters were 1.7–3.3 times greater

than those for all construction workers during 1992–2001. Rates

for welders and cutters showed an increasing trend, from 23.7

per 100,000 full-time workers in 1992 to 45.4 in 1997. The 2001

fatal injury rate of 39.9 per 100,000 full-time workers was 3 times

the rate for all construction workers and represented a 68%

increase from 1992. BLS reported 257 fatal occupational injuries

among welders and cutters during this 10-year period—an average

of 26 fatalities per year. (Sources: BLS [2002b,c]; Pollack and

Chowdhury [2001]; Chowdhury and Dong [2003].)

Nonfatal Injuries and Illnesses

How did the rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and

illnesses for welders and cutters compare with those for

all construction workers during 1992–2001?

Figure 4–52. Rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses

involving days away from work for welders and cutters

and all construction workers, 1992–2001. During 1992–2001,

rates of nonfatal occupational injuries and illnesses involving

days away from work for welders and cutters show an overall

decreasing trend, ranging from 573 per 10,000 full-time

workers in 1994 to 171 in 2001. BLS reported 21,940 nonfatal

occupational injuries and illnesses among welders and cutters

during this 10-year period—an average of 2,194 nonfatal cases

per year. (Sources: BLS [2002c; 2003b]; Pollack and Chowdhury

[2001]; Dong et al. [2004].)

References

BLS [2001]. Current population survey. Washington, DC: U.S.

Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. [www.bls.gov/cps/] and [www.bls.census.gov/cps]

BLS [2002a]. Survey of occupational injuries and illnesses. Washington,

D.C.: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics,

Safety and Health Statistics Program. Nonfatal (OSHA recordable)

injuries and illnesses. Industry incidence rates and counts.

[www.bls.gov/iif/oshsum.htm]

BLS [2002b]. Census of fatal occupational injuries. Fatal injuries.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor

Statistics, Safety and Health Statistics Program. [www.bls.gov/iif/oshcfoi1.htm]

BLS [2002c]. Current population survey. Washington, DC: U.S.

Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. [www.bls.gov/cps/] and [www.bls.census.gov/cps]

BLS [2003a]. Census of fatal occupational injuries. Fatal injuries.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor

Statistics, Safety and Health Statistics Program. [www.bls.gov/iif/oshcfoi1.htm]

BLS [2003b]. Survey of occupational injuries and illnesses. Nonfatal

(OSHA recordable) injuries and illnesses. Case and demographic

characteristics. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor,

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Safety and Health Statistics Program.

[www.bls.gov/iif/oshcdnew.htm]

BLS [2003c]. Survey of occupational injuries and illnesses. Nonfatal

(OSHA recordable) injuries and illnesses. Number of nonfatal

occupational injuries and illnesses with days away from work

involving musculoskeletal disorders by selected worker and case

characteristics, 2001. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor,

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Safety and Health Statistics Program.

[www.bls.gov/iif/oshwc/osh/case/ostb1154.pdf]

Census [2003]. County business patterns—United States: 2001.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and

Statistics Administration, U.S. Census Bureau. [www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/01cbp/cbp01-1.pdf]

Chowdhury RT, Dong X [2003]. Analysis of census of fatal occupational

injuries (CFOI) data, 1992–2001. Silver Spring, MD: CPWR – Center for Construction Research and Training. Unpublished.

Dong X, Men R, Hu H, Chauhan J, Gittleman J [2004]. Trends in

work-related deaths and injury rates among U.S. construction workers,

1992–2001. Washington, DC: CPWR – Center for Construction Research and Training (CPWR). Unpublished.

MSHA [2002]. Quarterly employment and coal production,

accidents/injuries/illnesses reported to MSHA under 30 CFR Part

50, 1991–2000. Denver, CO: U.S. Department of Labor, Mine Safety

and Health Administration, Office of Injury and Employment Information.

[www.msha.gov/STATS/PART50/p50y2k/p50y2k.HTM]

MSHA [2003]. Quarterly employment and coal production, accidents/

injuries/illnesses reported to MSHA under 30 CFR Part 50, 1991–

2000. Denver, CO: U.S. Department of Labor, Mine Safety and Health Administration, Office of Injury and

Employment Information. [www.msha.gov/STATS/PART50/p50y2k/p50y2k.HTM]

NCHS [2002]. Multiple-cause-of-death public-use data files. Hyattsville,

MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

[www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/elec_prods/subject/mortmcd.htm]

NIOSH [2002]. National surveillance system for pneumoconiosis

mortality. Morgantown, WV: U.S. Department of Health and

Human Services. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention,

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. Database.

NIOSH [2003a]. Surveillance, statistics, and research support activity

(SSRSA). Pittsburgh, PA: U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National

Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. [www.cdc.gov/niosh/mining/]

NIOSH [2003b]. Mining surveillance and statistical support activity

(MSSSA). Spokane, WA: U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National

Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. [www.cdc.gov/niosh/mining/]

NIOSH [2003c]. Analysis of 33 volunteer sand and gravel operations,

1999–2000. Pittsburgh, PA: Department of Health and Human

Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute

for Occupational Safety and Health. Unpublished.

Pollack ES, Chowdhury RT [2001]. Trends in work-related deaths

and injury rates among U.S. construction workers, 1992–1998. Washington,

DC: CPWR – Center for Construction Research and Training.

Royster LH, Thomas WG [1979]. Age effect hearing levels for a

white nonindustrial noise exposed population (ninep) and their use

in evaluating industrial hearing conservation programs. Am Ind Hyg

Assoc J 40:504–511.

Royster LH, Driscoll DP, Thomas WG, Royster JD [1980]. Age effect

hearing levels for a black nonindustrial noise exposed population

(ninep). Am Ind Hyg Assoc J 41:113–119.